The Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (ChZO), most of which is located in the Kiev Region, can be reached from Kiev by car in an hour and a half or two hours. This is an area of small villages and hamlets which, as you approach the Zone, give way to nothing but forest. At the Dityatki Checkpoint, those venturing this far will encounter several policemen, three ginger cats, and a red dog. The checkpoint sits on a peculiar boundary – a barbed wire fence, which stretches away from it into the fields on either side. The policemen check our passport details against those on the list sent in advance. Legally, only local workers and relatives of squattterrrs can enter, along with tourists, who are permitted to enter strictly in the company of a guide. In 2009, this area featured in Forbes magazine’s list of the twelve most exotic tourist destinations in the world, alongside Antarctica and North Korea. In some spots, radiation levels exceed the permitted dose by thirty times, but this does little to deter the curious from coming to see the planet’s most large scale monument to manmade catastrophe. Over the last ten years, forty thousand tourists have visited the ChZO. The flow increased substantially after the 2007 release of the popular computer game S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, whose action is set in the environs of the ChAES (Chernobyl Atomic Energy Station). Since then, illegal entrance has increased too: around 400 stalkers are detained each year, to receive a 400 hryvnya fine (around 1.2 thousand roubles, or €16) for breach of administrative regulations.

The territories of the Ukrainian SSR, Belorussian SSR and Russian SFSR that were subject to radioactive contamination as a result of the accident at the Chernobyl power plant were divided into four categories: the exclusion zone, the zone of absolute (mandatory) resettlement, the zone of guaranteed voluntary resettlement, and the zone of residence with preferential social and economic status. The exclusion zone covers those districts which experienced a compulsory evacuation of population in 1986 and 1987. The total area of the Russian exclusion zone is 310 km², with a further 11,500 km² falling under the other three categories for radiation risks.

That part of the Exclusion Zone located across the border in Russia forms part of Bryansk Region, and contains four villages with a combined population of 186 persons.

In neighbouring Belarus, the Zone is much wider and covers territories formerly inhabited by 22,000 people in 92 settlements. In 1988, the Polesia State Radioecological Preserve was created on these contaminated lands, a site for experimental beekeeping activities as well as horse rearing. Populations of wild bison, lynx, and Przewalski horses also roam the territory.

The Ukrainian part of the Exclusion Zone (with a radius of 30 km) covers several contiguous districts of Kiev and Zhitomir Regions. The total area of the territory, which was home to 116,000 people in 94 settlements prior to the disaster, comprises 2,600 km², an area slightly larger than Moscow. The length of its external perimeter, with its barbed wire fence, checkpoints and radiation-monitoring points, is around 440 km (the approximate distance between Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod, or Paris and Amsterdam). Inside the ChZO, certain regions are subject to a special access regime, covering tens of square kilometres within the Zone and the area in the immediate vicinity of the power station.

Today, Chernobyl is a city frozen permanently in Soviet times. Small, with clean and empty green streets, made up of inconspicuous grey two-storey buildings, Chernobyl lies in a dreamlike state. Before the accident at the ChAES, the population reached around 13,000 people, now fallen to a mere 4,000 (the entire ChZO is home to 5,000). Only rarely do you come across another human being here, and local traffic is limited to an old Soviet bus which drives around the streets several times a day for the workers. There are few inhabited buildings here – a few dozen, mostly concentrated in the centre. But the infrastructure of the town, despite the almost total exclusion of this settlement, continues to develop, albeit very slowly. The flow of tourists has given birth to a new demand and supply – the city is beginning to take on a second life.

In the building of the abandoned bus station and fire brigade headquarters, village shops are open for business, selling mostly essential supplies (including alcohol, of which a wide assortment is on offer). Payment can even be made by credit card and there are souvenirs for sale: tee-shirts with the legend “Chernobyl”, “apocalyptic” fridge magnets with depictions of the power station and nuclear mushroom clouds, and pink pens with radioactivity symbols on. Two hotels have opened in the town: one in a refurnished former boarding house (with small three to four person rooms), and the second in a house once occupied by Party workers (a seven person room in a renovated three-room flat). The large Soviet canteen is in operation, and the Desyatka café opened its doors quite recently, providing a place to eat cheaply and use Wi-Fi in the bar. A curfew is still in place, though the locals no longer appear to take it particularly seriously.

The present day inhabitants of Chernobyl are mostly forestry workers, ecologists, scientists, technical personnel at the power station, and Ukrainian Interior Ministry officials who guard against illegal penetration of the 30 km² zone. Chernobyl itself holds the basic industries engaged in keeping the territory in an ecologically safe condition. They monitor the radioactivity of the waters of the River Pripyat, its tributaries, and the surrounding air. A rotating scheme is employed – “4 for 3”: staff arrive on Monday by bus, to be taken away again on Thursday, when they return to the “wider world”. Some specialists work according to another system – “15 for 15”: spending a fortnight in the Zone, and the rest of the month at home. People come to work here from various parts of the Ukraine, though the majority are from Kiev Region. 22 year old Dasha from Vinnitsy Region works in Chernobyl’s café, having been unable to find any other employment during the Crisis. Dima the cook, on the contrary, actually wanted to come and work here, due to the high wages for Ukrainian standards. A bonus is added to the main salary here, because of the harmful working conditions. In the evenings, the locals traditionally gather to eat at the Desyatka café, watch the television and discuss the latest news – events in the eastern Ukraine, the Euromaidan, and the Crimean referendum.

Chernobyl’s foundation date is considered to be 1193, when the place was first mentioned in the Ipatievsky Chronicle. With the formation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569, the town came under its rule. Later, in the 18th century, Chernobyl was annexed to the Russian Empire as a township of the Kiev Governorate’s Radmomyshl Division, going on to become a major river traffic terminal. In 1921, Chernobyl became part of the Ukrainian SSR, and two years later, a centre of a district of the same name (receiving urban status in 1941). After 1990, these places began to attract pilgrims – religious Jews, who rebuilt the tombs of the zaddiks or holy men buried here. Services have been held in the single functioning Orthodox congregation in the exclusion zone – that of Saint Ilya’s Church - since 2001.

The idea of putting the “peaceful atom” in the service of the Soviet national economy was first aired by Academician Kurchatov – the creator of the Soviet atomic bomb. Active construction of nuclear power stations in the USSR began in the seventies, and would soon, in just one decade, come to provide 15% of all energy generated in the country. The Chernobyl Atomic Electroenergy- Station (ChAES) was the pride of the Soviet Union: by 1986, it was the most powerful nuclear power plants in the country and one of the most powerful worldwide. The USSR compared its successes in atomic energy to its achievements in the field of space exploration. Nobody was in any doubt that the future of energy lay with nuclear power.

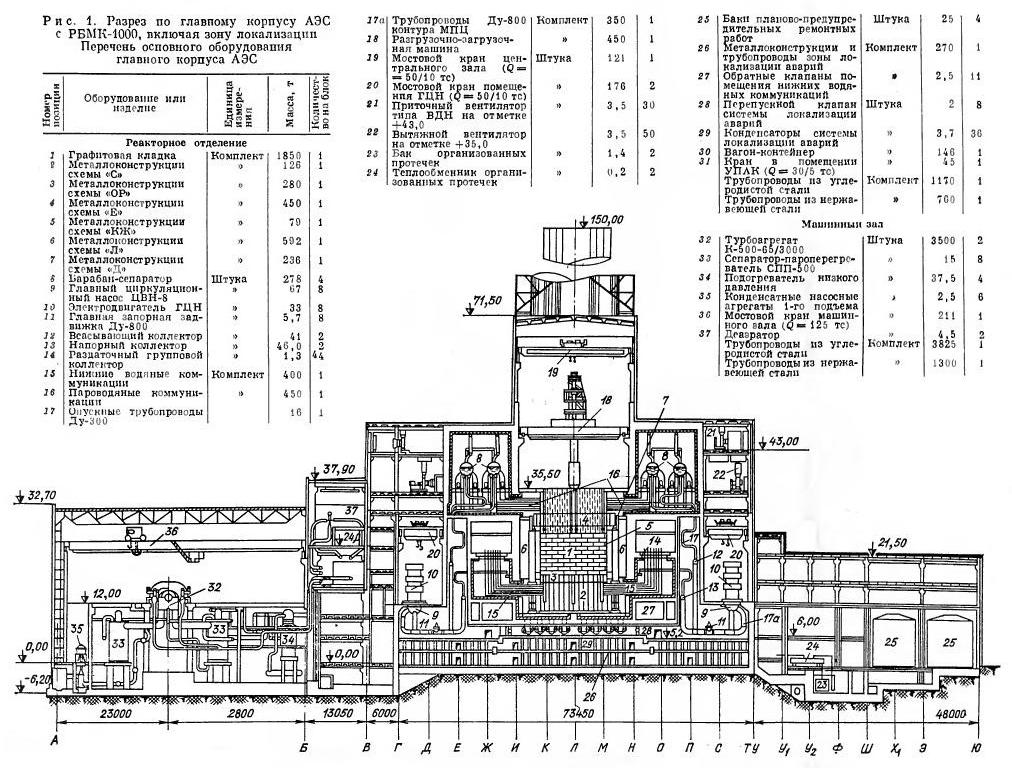

The construction of the ChAES began in March 1970. The station became the third in the USSR to have graphite-water reactors of the RBMK-1000 type, following in the wake of the power stations at Leningrad (launched in 1973) and Kursk (1976). Chernobyl belonged to the single-loop variety of AES: supplied by turbines, coolant (water) formed steam when passing through the reactor. In the period from 1978 to 1984, four generator units were brought into use. The third construction stage (the fifth and sixth generator units) was called to a halt in 1987. At the moment of the accident, the station was producing 150.2 billion kWh of electrical energy, and was still producing 158.6 billion kWh at the time of its final decommissioning on the 15th December 2000. By that point, 9,500 people had worked at the station.

Eleven reactors of the so-called Chernobyl type (the RBMK-1000) reactors are currently in operation worldwide, all in the Russian Federation: at Kursk, Leningrad and Smolensk. A further AES with the same kind of reactor, Ignalina in Lithuania, is not now in use. Another reactor of this same type at the Kursk AES was never completed and, most likely, will never be put into operation. Since the accident at the ChAES’s fourth generator unit in 1986, two other serious incidents have taken place at stations equipped with RBMK-1000 reactors. In 1991, a fire broke out in the machine hall of the second generator unit at Chernobyl, and, in 1992, there was a breach in the fuel channel at the Leningrad AES. There were no casualties.

(here and subsequently all times are local time). At the Chernobyl AES, the fourth generator unit is shut down for regular repairs, during which an experiment would be carried out. This would have shown whether the mechanical inertia of the turning of the turbo-generator’s rotor could be used for short-term production of electrical energy during sudden shutdowns of the reactor.

The level of power of the reactor required to hold the planned experiment, 700 MW, was reached, though it continued to fall, reaching 30 MW in half an hour. At such levels, immediate shutdown of the reactor should have been effected, but the operator pulled out the reaction inhibitor rods in an effort to boost the power level back up.

The experiment was begun at an inadmissibly low power level of 200 MW. In several seconds, the reactor’s power level shot up sharply by one-hundred times. The operator pressed the emergency button which should have shut down the reactor.

The first thermal explosion, blowing off the upper part of the reactor – a slab weighing 1,000 tonnes. In several seconds, a second explosion completely destroyed the reactor, flinging 190 tonnes of radioactive material into the atmosphere, including isotopes of uranium, plutonium, iodine and caesium. Two employees at the station were killed, and more than thirty fires broke out in the surrounding area.

The power station’s Special Fire Brigade (SPCh-2) received the signal that a blaze was underway, and began to extinguish the fire. Auxiliary fire fighting teams were also sent to the station. The struggle to put out the fire lasted five hours, involving the mobilisation of 15 fire teams from Pripyat, Kiev, and the wider region. The firemen did not have the necessary protection.

Viktor Bryukhanov, the director of the ChAES notified the second secretary of the Kiev Regional Committee about the explosion and fire, lying that the radioactivity situation in the town of Pripyat and at the AES presented no danger to life.

A government committee arrived at the scene of the catastrophe, headed by Boris Shcherbina, deputy chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers.

The Soviet Health Ministry resolved that the emergency evacuation of Pripyat was necessary.

Pripyat’s radio transmission network announces the round up and temporary evacuation of the townsfolk. 50,000 people were shipped out of the town with virtually no belongings: they fully expected to return soon. Helicopters began the work of covering the damaged reactor with absorbent materials, including boron-carbide.

The presenter of the programme Vremya read out the first official TASS report: “An unfortunate incident has taken place at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. One of the reactors has suffered damage. Measures are being taken to remedy the consequences of the incident. Those affected are receiving the necessary treatment. A government committee has been formed to investigate the occurrence.” The Foreign Affairs Ministry summoned a press conference to inform foreign journalists of the catastrophe.

In Kiev, where radiation levels were exceeding the allowable norms, mass celebrations were held to mark May Day.

The evacuation began of the inhabitants of the zone within 10 kilometres of the reactor, increased two days later to a 30 km radius.

Large-scale decontamination work was begun, for which people and equipment were gathered from all over the USSR.

Mikhail Gorbachyov spoke on national television, making an official announcement about the accident.

In the immediate aftermath of the reactor explosion, 31 people died – station personnel and firemen. The majority of the station staff died within three months, having received doses over 4,000 mSv (a lethal dose). The number of those who perished subsequently due to oncological problems caused by radiation is still not clear and remains a topic of bitter dispute. 530,000 people received doses from 10 to 1,000 mSv. These were people who had been in the contamination zone for extended periods of time: soldiers, rescuers, technicians and AES staff members. According to the most conservative estimates of the Chernobyl Forum, 9,000 people have died and around 200,000 are suffering from illnesses caused by the accident at the ChAES. 2005 data from the Ukrainian Health Ministry for the period from 1987 to 2004 gives a figure of 530,000, only referring to Ukrainian citizens who have died from the impact of the accident. A law was passed in 1991 on the social welfare of citizens suffering due to the catastrophe. Up until the present, around 7 million people in Russia, Belarus and the Ukraine have been recognised as “Chernobylers”.

The pond surrounding the ChAES is an artificial body of water that was created to cool the station’s reactors. It contains great quantities of fish. Workers from the neighbouring facilities and any tourists who happen to be around never miss the opportunity to feed the two-metre long catfish.

The first measure taken to deal with the impact of the accident on the local population was the administering of an iodine prophylactic, which, however, was only implemented speedily in Pripyat – on the very day of the disaster. The evacuation of its inhabitants only began in May – extending to a zone within 10 and 30 kilometres radius of the power station. Of the 400,000 people living in the exclusion zone and areas of “strict radiation control”, 116,000 were evacuated in the spring and summer of 1986, with a further 270,000 were resettled in following years.

In May 1986, special measures were initiated to decontaminate settled areas and technical facilities in the Exclusion Zone, including the sanitary processing of buildings and streets, the removal of the upper soil layers, and the burial of contaminated machinery.

Then the specially-organised construction bureau №605, under the Ministry for Medium-Size Engineering Manufacture, began to build a sarcophagus around the critical reactor (the “Shelter” installation). By November of 1986, construction of the sarcophagus had been completed. Over 100,000 cubic metres of concrete had been used in its erection, along with 6,800 tonnes of steelwork. Up to 95% of the fuel that had been present in the reactor at the moment of the catastrophe remained inside the “Shelter”.

The amount of radioactive materials reached 185-200 tonnes, with a total activity level of 16 million Curie units. That said, no more than 60% of the area of the “Shelter” has been examined since 1986, with the remainder being inaccessible due to the hazardous radioactivity field and the obstacles produced by the explosion and collapse of internal ceilings.

350,000 people took part in the initial works to combat the consequences of the accident in 1986 and 1987, with the total number of clean-up workers estimated at 600,000.

In the period 1986-1991, the USSR spend a total of $18 billion on the clean-up operation, 35% of which was allocated to social aid for the afflicted and 17% to the resettlement. The station itself was only decommissioned completely in 2000.

The new safe confinement which will cover the old sarcophagus

Consideration had already been given as far back as 1989 to the need to modify the erected sarcophagus, rendering it a safer structure. At that time, the staff of the Kurchatov Institute for Nuclear Energy had put forward the concept for the construction of a new structure over the existing “shelter”, to ensure the total isolation of the damaged generator unit from the external environment. In 1991, further proposals were made for alternative approaches, involving complete sealing, total dismantling, or filling the sarcophagus with concrete. Following an international competition for projects to modify the “shelter” into an ecologically safe system, the Ukraine categorically ruled out the creation of a waste repository on the site of the fourth generator unit in 1996, despite the criticisms voiced by Russian specialists.

In 1998, with the support of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and a group of international donors, implementation was begun on the Shelter Implementation Plan (SIP), comprising the construction of a new safe confinement structure (the NBK or Shelter-2) and a repository for the depleted nuclear fuel.

The tendering process for the construction of the NBK was announced on television in 2004, with the American engineering consortium Bechtel-Battelle Memorial emerging as the winner, in association with the subcontractor SP Novarka, an Italian, American and Turkish company specially founded for the project. These had produced a complex design, featuring a protective cupola-arch and equipment to extract radioactive materials from the damaged generator unit. To ensure the builders’ safety, the arch (measuring 108 m in height, with a length and width of 162 and 257 m) was to be built not in-situ over the dangerous reactor but on a specially equipped platform beside it. Once work on it was completed, the 29,000 tonne NBK was moved on rails to its position over the old sarcophagus and then sealed. Unlike its predecessor, the new sarcophagus is intended to have a lifespan of one hundred years.

Video by the MAMMOET company

The confinement should have come into operation by the 15th October 2015 (the date on which the contract expired), but the timetable for completion of the construction had already been shifted several times, due, among other factors, to problems with financing. The initial cost estimates for the entire SIP project were €550 million, but had grown to €1.6 billion by 2011, of which around €935 million was spent on the sarcophagus alone. By then, €864 million had already been provided by the EBRD and donor countries, and, at an international summit marking the 25-year anniversary of the disaster, Kiev managed to gather together the greater part of the funds needed – a further €550 million, which, the Ukrainian side assured, would permit the building work on the new sarcophagus to be completed according to plan.

Information on the progress of construction up to the 26th April 2015:

On the 17th March 2015, Vince Novak, director of the EBRD’s department for nuclear safety, declared that around €615 million was still needed to complete the building work. In his words, EBRD shareholders had allotted €350 million, a further €165 million was awaited from the Big Eight countries and the European Commission, and the remaining €100 would be provided by other donor countries. The timescale for building the NBK was extended once more – works now being planned to end by March 2017. Under these circumstances, on the 9th April, the Chernobyl AES was officially converted to decommissioned status.

The construction delays may become critical: the maximum use life of the “Shelter” comes to an end in 2016. There is a real danger of a breach in the old sarcophagus. Therefore, on the 12th February 2013, due to the build-up of snow, ten wall panels and the light roof of the machine hall at the fourth generator unit broke. Work on erecting the new sarcophagus was halted for a week, until the French builders received confirmation that it was safe to continue.

Ultimate disassembly of the fourth generator unit is planned for 2065. By then, a complete dismantling of the reactor pile assembly should have been carried out, along with a clean-up of the platform and the disposal by burial of the fuel-containing materials found in the fourth generator unit. How exactly this will take place is not yet clear. On the website of the Chernobyl AES specialised state enterprise, referring to the international expert coordinating group, it is explained that, for the moment, devising a strategy for the extraction would be “inexpedient, in so far as superior and safer techniques for dealing with high-level radioactive waste may appear in future”. It has therefore been tentatively decided to put aside the question of extraction until such time as a repository has been created for the final burial of the waste, “that is, in several decades time”.

While approaching Pripyat, the radiation dosimeter begins to beep more and more often. Standing at a fork in the road is the entrance marker “Pripyat 1970” (one of the main tourist photo spots), beside an inconspicuous yellow sign saying Rudii Lis (“Red Wood”). This spot is one of “eternal autumn”: the trees appear dried out, with leaves of a pale orange hue. During the explosion at the ChAES, the main expulsion of radioactive dust was in the direction of Pripyat. In a mere matter of days, the forest reddened, after which part of it was felled and buried.

Before entering the territory of the town, you have to pass through another checkpoint – “Lelev”, where the guides hand over to the guards the documents indicating permission to visit these places. The main recommendations to tourists are: to stay together, not to enter the dangerous buildings, preferably to wear gloves, touch nothing, carry a dosimeter and eat nothing. Though the level of radioactive contamination has fallen over the last three decades, radioactive dust can still be found all over the place: under your feet, on the walls, and on the trees.

In its heyday, Pripyat was a model Soviet town with a well thought-out and self-sufficient infrastructure. 15 day nurseries were built here, 5 schools, 25 shops, cafés, restaurants, a hospital, river wharf, hotel, Palace of Culture, cinema and a swimming pool. There were four industrial enterprises active in the town, including the Jupiter factory, which produced tape-winding mechanisms for cassette recorders (both for domestic and special purposes). It was a matter of prestige to live and work here, and the salaries paid were rather high for the period.

The city of Pripyat was founded on the 4th February 1970 on the river of the same name, a tributary of the Dnepr, at a spot 18 km from Chernobyl, as a home for the workers engaged in the construction of the power station, 3 km away (becoming, from 1979, a city subordinate to the Regional administration). Construction of the town and station was declared an all-Union Komsomol top-priority project, and so the main body of its citizens was drawn from the ranks of Komsomol members from all over the USSR. By 1986, the population of Pripyat had grown to almost 50,000, with an average age of 26 years. The city’s general development plan foresaw a potential population of up to 80,000 people.

Nowadays, nature is reconquering the territory of the abandoned town – the houses seem to have grown into a forest. Birches grow on the roofs and first floors of many buildings, their branches pushing through windows into old flats, and birds build their nests on balconies and in telephone booths. The most striking sign of nature’s victory is seen in the football stadium with its rotting wooden stands, high rusty floodlights and, in the centre of the pitch, a fully grown wood. The guides say that the confinement structure builders, living in Slavutich and coming to work by train, have a game – counting moose from the window. Their colleagues say that, in wintertime, wild boar may occasionally be seen running across the main square of Pripyat.

Nature is rich in these parts: here roam bears, otters, badgers, muskrats, lynx, deer, Przewalski’s horses, and wolves. Stories of two-headed beasts wandering the Exclusion Zone are myths. German and American scientists who have conducted research here have come to the conclusion that: despite the high levels of background radiation, mutations are observed among the fauna at roughly the same percentage relation (in some cases slightly higher) as in ordinary conditions.

Not a single house in Pripyat has escaped the looters. The town remained untouched only in the first few weeks after the accident at the ChAES. After that, people began to come here to cart away furniture, domestic items, even sawing away the iron rails from the staircases in some houses for the scrap metal. During the rapid evacuation process, the citizens had been simply unable to bring their valuables with them. In the bedroom of one of the flats we entered, the piles of discarded items and rubbish concealed the chemistry notes of a junior student with accurate diagrams highlighted in felt-tip; in the kitchen, there were dusty yellowed cookery magazines and an upturned stove; in the hallway – old women’s shoes; and in the large empty bedroom – a dusty torn divan. They left home and never returned – many who fled the town after the accident little realising that they would never again return to live here.

But there are some Pripyatchane who have returned home, as the years have passed, to see again their native land. One of the guides told how one time a former inhabitant came to Pripyat and went to the school he had attended back in 1986. He had wandered a long time through the classrooms and emerged two hours later, clutching his old exercise book, in which his teacher had given him a mark of “5” for the tasks assigned on Friday the 25th of April – just one day before the disaster.

One of the town’s five schools is found in a semi-derelict state, but the others are more or less intact for those wishing to explore. Hundreds of Soviet textbooks remain in the classrooms, piles of marking for the teachers, old maps, models of world landmarks (including the Kremlin), vessels of fish preserved in alcohol for use in biology lessons. There are children’s toys everywhere – dolls disfigured with age being one of the most popular symbols of the tragedy. There was a baby boom here in the 1980s: the young inhabitants had felt that their prosperous conditions were just right to raise a young family.

At the moment of the accident, around 20-20% of the town’s population was made up of children. The playroom of the day nursery is like a frozen snapshot: dolls sit facing one another, tin cars stand in rows beside towers of building blocks, weather-beaten soft toys and plastic Olympic mascot bears.

Alongside the school and the nursery, Pripyat’s hospital is one of the main tourist attractions. Its dusty corridors are littered with glass vessels, faded medical journals and sanitary “ducks”22222. Rusty beds stand in the wards, and in the operating theatre the table is still where it was, with the lamp hanging above it. The large foyer has the hospital timetable on the wall with its legend “Today’s patients: ...”, below which there are empty cells in a list of surnames. The first to get sick – the power station personnel and firemen – were brought here after the accident. On the first floor there still lies the helmet lining of one of the clean-up workers, with a radiation level of around 10,000 µR/hr (to be compared with a norm of 20-30 µR/hr).

Excursions in the exclusion zone have been officially permitted by the Ukrainian authorities since 2010. In 2011, however, a dispute arose between the Ministry for Emergency Situations and the Prosecutor-General’s Office: the latter had tried to forbid access to the zone, while the Ministry’s rescuers had apparently agreed otherwise. The logic of the Prosecutors and the security guards is understandable: Pripyat is falling derelict, though the buildings are strong they are transforming into ruins, the famous Ferris wheel is thoroughly corroded, and all this at any time might come crashing down on the heads of visitors. Nobody is planning to restore the city, and responsibility for the death of any tourists would fall upon the authorities and the guides.

The Energetik House of Culture is now in a dangerous condition: its roof is full of holes. And yet the foyer still preserves its murals. At the end of April 1986, the town was preparing for the May Day festivities. Here can be found portraits of Party leaders, along with an old piece of Edison audio equipment.

Pripyat is full of Soviet symbolism: the hammer and sickle decorates each lamp post, iron cubes bear depictions of Komsomol members, there are the old vending machines for carbonated water, and the lyrics of the Soviet anthem – “The Party of Lenin is the people’s strength. It leads us to the triumph of communism” – are virtually peeling off the wall of a nine-storey building.

For many tourists, greeted by the slogan Khai bude atom robitnikom, a ne soldatom (“Let the atom be a worker, not a soldier”) still in place over the main square, these sites are of interest as a peculiar monument to socialist realism or Soviet industrialisation. Others are drawn to Pripyat as an “apocalyptic” place, where there is no place for mankind following the devastation of a manmade catastrophe.

Only a few facilities remain in operation in the town – a specialised laundry, an iron-removal and water-fluoridisation station, and a garage for special equipment. They are staffed according to a rotating system. No independent settlers live in Pripyat.

The ChAES continued to function after the accident, and so the decision was taken to found a new satellite town to service the station. On the 2nd October 1986, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR and the Council of Ministers of the USSR signed a decree on the construction of the town of Slavutich. The first authorisation of settlement was issued on the 28th March 1988. Slavutich is the youngest town in the Ukraine and has a population of 25,000. Administratively it comes under the Kiev Region, despite being located completely within Chernigov Region. The average salary in the town (2013) is 5,653 hryvnya (22,600 roubles, or €302), and pensions are 3,587 hryvnya (14,300 roubles, or €161), both of which indicators are 1.5 or 2 times in excess of the analogous figures for the Ukraine as a whole. Since 1999, the Slavutich special economic zone has been functioning in the town (a preferential taxation scheme is to be introduced from the 1st January 2020). This system was introduced to help soften the social and economic consequences of the shutdown of the town’s backbone enterprise in 2000 – the ChAES. According to 2012 data, the special economic zone has attracted $42.7 million in investment, including $11.8 million from abroad.

Within the ten-kilometre radius it is impossible to find any abandoned village houses. Soon after the accident, the decision was taken to demolish and bury all structures in the contaminated area. Dozens of signs can be seen in this zone’s fields, bearing symbols indicating dangerous radioactivity levels, each standing on the site of somebody’s “buried” home. There are three burial sites for radioactive waste in the Exclusion Zone, and nine points for the temporary storage of such waste with a combined capacity of 4.8 million cubic metres.

The tractor and engine repair station (MTS) is situation by the buried village of Kopachi (which coincidentally translates as “Diggers”). The base territory is strewn with old agricultural machinery – Niva combines – and equipment used during the clean-up operation following the accident. The obstacle removal vehicle that was used to help fell the “Red Wood” now stands here too.

The probe of the IMP-2 decontamination device, used in the felling of the “red forest”, now radioactive to the turn of up to 12,000 microroentgen per hour (compared with a norm of just 20). The burial of the killed trees and upper layer of topsoil was carried out using dozens of pieces of special machinery: first the trees were cut down, then bulldozers buried them in trenches around one metre deep, filling them in with “clean” earth. In this way, over 4,000 cubic metres of radioactive material was buried.

A pine forest found within the ten-kilometre zone contains the Emerald campsite – once the main leisure centre for the children of the surrounding district. Small wooden cabins decorated with pictures of cartoon characters stand on a hill by the river, and a stage stands in the centre of the camp which once served as the venue for Pioneers’ theatrical performances. It is all very reminiscent of the large abandoned dacha settlement from the film Burnt by the Sun. Tourists and stalkers have a good chance of encountering wild animals here.

On the road from Pripyat to Chernobyl, a high “fence” is visible far off on the horizon – the Chernobyl-2 radar array. Up until last year it was forbidden to approach within even 3 km of this facility. The Chernobyl-2 radiolocation hub (RLU) was long considered secret, and is now an object of special conservation. The radar is 150 m high and 750 m wide. Beside it stands a two-storey building, 1 km in length – the installation’s control centre. Chernobyl-2 contained the RLU №1 radio reception centre and a military settlement (RLU №2 is located in the vicinity of Komsomolsk na Amur in the far east of Siberia). Their construction was completed by the mid 1970s as part of the major Duga (“Bow”) project, which was launched during the Cold War as an early warning system for missile attacks and to pinpoint the launch sites of intercontinental ballistic missiles on US territory.

The radar facility – satellite picture

From 1976 onwards, the station sent out radio impulses at a frequency of ten per second, which wedged themselves into civil frequencies, jamming worldwide communications systems. Its characteristic way of “tapping” away at the airwaves in the west earned this facility the nickname of the Russian Woodpecker.

The building costs for Chernobyl-2 amounted to 150 million roubles. The combined investment, covering Duga’s eastern ZGRLS 5N32 hub and the experimental ZGRLS 5N77 Duga-2 near Nikolayev, was over 600 million roubles.

Scheduled modernisation of the Cherbobyl-2 system was to have been completed by November 1986. After the accident at the AES, these territories lost their energy source and fell within the zone of radioactive contamination. The project was wound down, and the greater part of the military settlement’s inhabitants were evacuated at once. Chernobyl-2 remains to this day the sole preserved object of ZGRLS Duga: the antenna arrays at Nikolayev and in the Far East have since been dismantled.

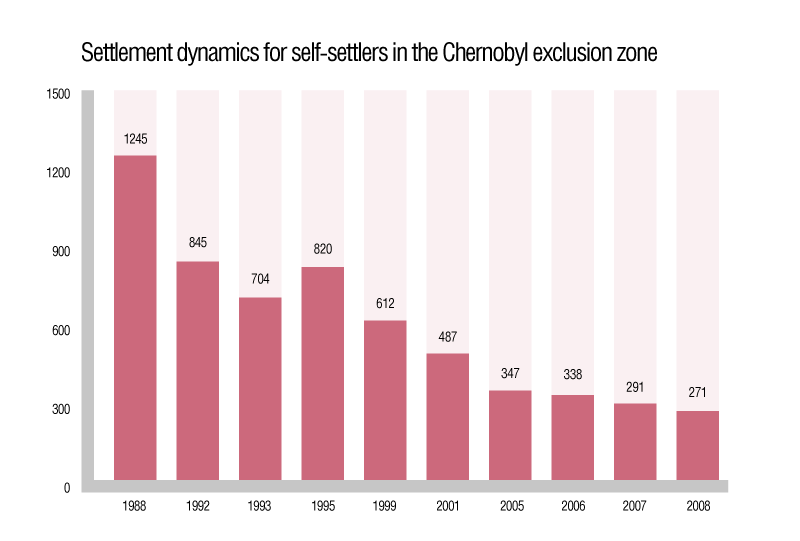

At the present time, around 300 samosely or “squatterrrrs” live in eleven settlements inside the Exclusion Zone – people who have returned of their own will to live in the abandoned houses. A village might have just one inhabitant, while the next could have three or four families in residence. The most famous samosel in the Chernobyl Zone is probably Granny Hanna. She takes offence at the term “self-settler”, however, as she has lived here all her life, simply returning to her own home. Background radiation levels in this village have now fallen to normal, but the land remains contaminated all the same.

83 year old Baba Hanna lives in the abandoned village of Kupovatoye with her 75 year old sister, who has been an invalid since childhood. They returned home almost immediately after the evacuation: Baba Hanna was unable to get used to living in town. There are four homesteads in the vicinity, one of which is home to her cousin Sofia. Baba Hanna has a small plot: a vegetable garden, a small garden and fourteen hens. Her problems are those typical of a simple villager: two years ago her chickens were engulfed by the winter snows, and wolves mauled her only dog. There are no shops here, but a car loaded with provisions comes twice a week. She steadfastly puts up with all difficulties, coping practically single-handedly with her work. The local police make periodic visits to the inhabitants, helping them with their husbandry. Granny Hanna is always happy to receive guests, but shoos away persistent tourists wanting their photograph taken with her, jokingly referring to them as “maniacs”.

People began returning to their homes literally a few weeks after the explosion at the ChAES: some didn’t understand what radiation is, others thought it was just scare-mongering, and some didn’t want to leave their property, or simply preferred to die in their own home. In 1986, there were already 1,200 samosely, a figure that has now grown fourfold. 85% of those living here are aged over sixty. No children are born in the exclusion zone, though there have been exceptions to this rule too. On the 25th August 1999, a daughter Maria was born to the “self-settlers” Mikhail Vedernikov and Lidia Sovenko – the first and only child of the zone. She no longer lives within the bounds of the ChZO.

In his research, Denis Vishnevsky, an employee of the Chernobyl Radio-Ecological Centre special state research and production enterprise, writes “The most characteristic trait of these people is their total lack of radiophobia. The system of arguments is simple and clear: “radiation cannot be seen and cannot be heard”, “the cat gives birth to lots of perfectly normal kittens”, and “we have no health problems”. The second characteristic trait is their self-sufficiency: they do not complain to the authorities and ask nothing of them. They look at everything with the wisdom of people who have extensive life experience and who have made their own important life choice”.